by Claire Renkin

Perhaps it is a sign that one is getting older, but the season of Lent seems to arrive before we have recovered from the festivities of Christmas. Barely have shops and supermarkets tucked away Christmas decorations before first Easter eggs and then hot cross buns emerge, ready to be consumed. Ironically, marketing turns upside down what centuries of reflection on the central mystery of our Christian faith teaches us: through death we are reborn to new life. Lent culminates in Holy Week, traditionally known as Passiontide, when we enter into the events of Christ’s passion, death and resurrection.

Michelangelo

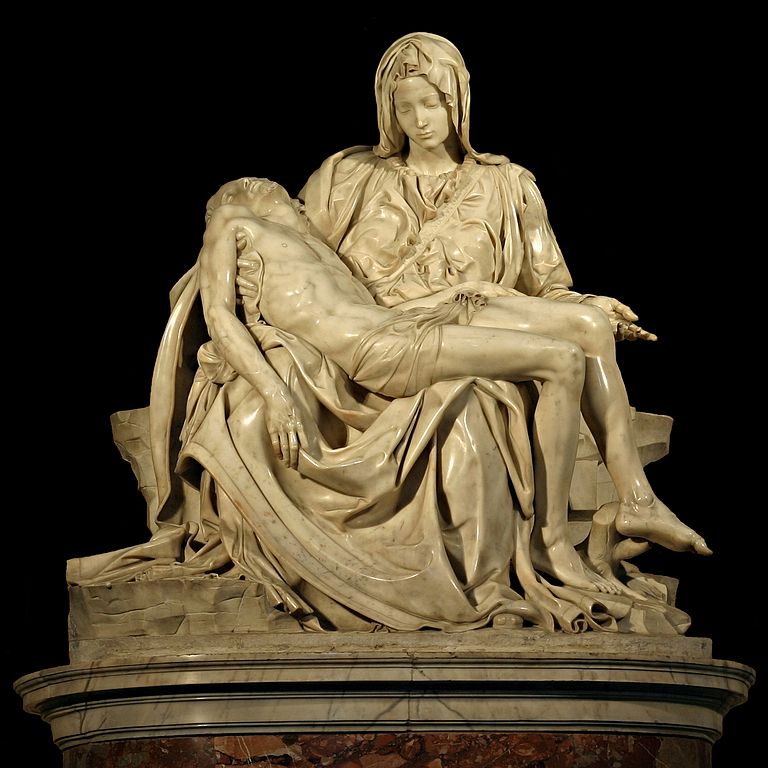

Although the gospels present us with disturbing accounts of the violence and brutality of Christ’s treatment, visually one of the most compelling images of Christ’s suffering portrays a moment of pain and loss that is stunningly gentle and serene. Michelangelo’s Pieta was sculpted by the young Florentine in the years 1497–1500. Originally the work was commissioned by a French cardinal, who wished it to be placed in his funerary chapel in St Peter’s. As we behold this sculpture, our gaze joins with that of Christ’s grieving mother, encouraging our eyes to move slowly over the slumped and lifeless form. Mary’s lap becomes a temporary resting place where, together with her, we pause in this moment between the deposition and the entombment. Michelangelo gives us a Christ whose idealised body recalls not only the influence of the classical past but also the phrase familiar from the canon of the Mass where we imagine Christ as a perfect and spotless victim.

For sculptors, the task of persuading us that a mother could plausibly contain the full-grown form of her dead son was a difficult one. Michelangelo convinces us of this almost physically implausible action by endowing the Virgin with garments that mass and swell around her form, so that she becomes able to support her dead child. The mood of profound and intimate contemplation is captured in the Virgin’s downcast gaze and slightly inclined head. But perhaps most of all what evokes the grief of the Virgin’s loss is her youthful beauty. Not only is Christ’s mother impossibly young; she also appears disturbingly remote. Here lies the spiritual and artistic power of Michelangelo’s genius. Not only do we reflect on this moment from the passion, but because of the incongruity between the Virgin’s ageless beauty and her maturity as a mother, we recall the more joyful images of her holding her newborn child. In collapsing the event of birth and death into this one timeless moment, Michelangelo evokes not only the desolation and sorrow of the Virgin at the moment she received her son’s lifeless body, but also the suffering of every mother who has felt the pain of the loss of a child.

Holbein

Anne Hunt reminds us that often we tend to pass too quickly from Good Friday to Easter Sunday. In our meditation on the Passion, the starkness of the Good Friday liturgy can help us enter into the events of Christ’s suffering and death. But Holy Saturday is another story. It is precisely because, in one sense at least, nothing seems to happen that we are often left unable to find a way of understanding this harrowing period in Christ’s journey from death to new life. By focusing attention on the inertness of Christ’s corpse, Holy Saturday dramatises God’s total embrace of humanness.

Holbein the Younger’s Body of the Dead Christ in the Tomb, painted in 1521, reveals, with unflinching accuracy, an image of Christ’s body laid in a tomb. This image evokes both the physical and spiritual experience that Christ embraced for our sakes. Holbein shows us a body detached from any of the comforting details that so often accompany images of the dead Christ: no faithful mourners, not even lamenting angels to remind us of God’s merciful love.

Instead, Christ’s body is unceremoniously laid out in a shallow tomb. The emphatic horizontality of the space that encloses the lifeless body, together with the uncompromising rendering of the details of death (note how the face, hands and feet have already taken on a greenish hue), convince us of the mystery of utter annihilation that Christ descended into on Holy Saturday.

Bellini

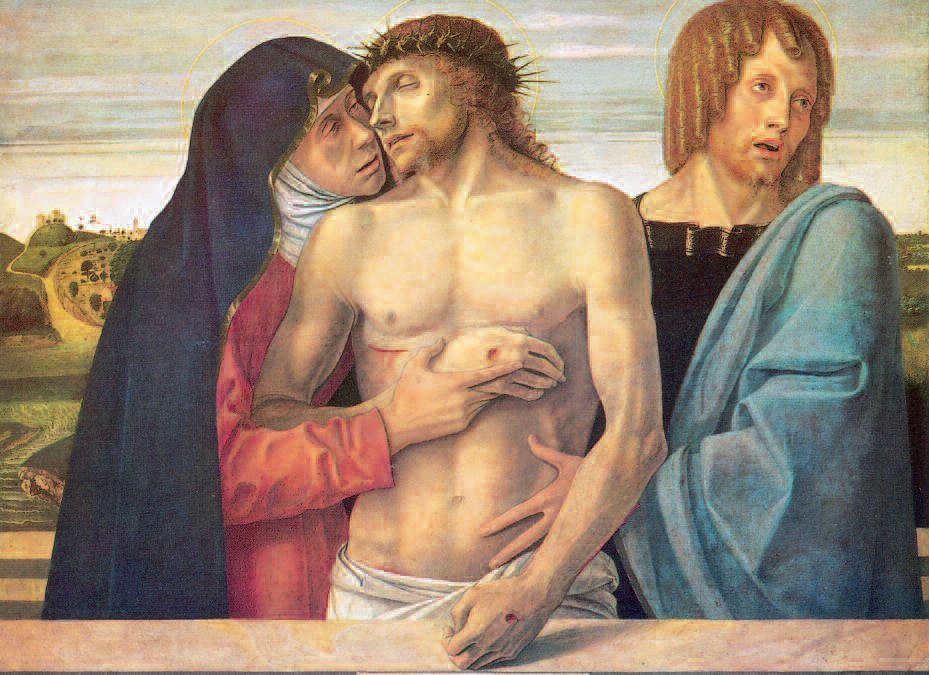

Giovanni Bellini (1430–1516), the great Venetian artist of the Renaissance, painted altarpieces, mythological scenes and portraits. Among his religious devotional works, the theme of the Pieta would occupy him throughout his long career. One of the most moving and hauntingly beautiful interpretations of this scene is the version dated between 1465 and 1470, now in the Brera Museum, Milan.

The dead Christ is held upright, supported by his mother and St John the Evangelist. They appear to stand behind a low stone parapet, which divides the space of the viewer from the sacred scene before us. Behind the figures we glimpse a landscape devoid of human presence—even the land is in mourning. Bellini captures with acute sensitivity to light and texture the grim reminders of Christ’s passion, from the disturbingly delicate crown of thorns to the fresh wounds in his hands and side. But it is surely the great master’s capacity to portray profound grief that moves us most. The faces of the mother and child are brought together before the moment of separation. Mary’s head turns toward Christ’s face as she gazes with the utmost sorrow on the exhausted face of her dead son. Her lips are parted as if she is about to utter a final lament for the suffering she and others have just witnessed. In a gesture of great tenderness, her hand supports her son’s lifeless arm. The overlapping hands in the centre of the painting offer a poignant testament to Mary’s steadfast love.

Giotto

Lent, Passiontide, Easter, together with Christmas, comprise the great seasons of the Church. Arguably the visual arts have been more successful at capturing the drama of the passion than that of the resurrection. Although artists frequently include the resurrection in cycles of Christ’s life, inevitably it is the scene of the crucifixion or the lamentation that moves us. One of the exceptions to this generalisation is Giotto’s fresco of the resurrection from his cycle of Christ’s life in the Arena Chapel, Padua. Giotto painted the frescoes for the private chapel of Enrico Scrovegni between 1304 and 1313.

In a scene that combines majestic mystery and spiritual insight, Giotto visualises the resurrection as a theological event that is truly the culmination of the incarnation. The artist does not attempt to convey the mystery at the heart of the resurrection, Christ’s triumph over suffering and death. Instead we see two angels sitting on either end of the tomb. The hand of the angel on the left hovers outstretched, rhetorically confirming that the space both above and below stands empty. The other angel signals to us by gesture and glance where we are to find the risen Lord. As if enacting our response, the Magdalene stretches out her arms in a gesture that conveys both longing to touch her Saviour and understanding that she cannot. Bewildered in similar fashion, we behold the resurrected Christ. His upper body turns toward the Magdalen, yet we see by the placement of his foot that he also turns away from her. In this eloquently ambivalent pose, Giotto expresses the spiritual and human essence of the resurrected Saviour. Wholly human, alert and alive to our longings and desires, yet also divine, the conqueror of death and sin holds a banner in his left hand as he prepares to depart. He leaves us facing the same challenge as he left with the Magdalen. In the words of Hippolytus, third-century bishop of Rome, she was about to become ‘apostle and truth’.

Claire Renkin has been teaching art history and spirituality at Yarra Theological Union since 2001. Her teaching areas include the art and architecture of the early Christians and Byzantium, and the art and spirituality of the late middle ages. In addition to these topics, Claire co-teaches units on women doctors of the Church, death, dying and bereavement in art and spirituality, and the history of Mary in the Christian tradition.

This article was first published in The Summit in February 2004.