1 Samuel 3:9; John 6:68c

Alleluia, Alleluia!

Speak, O Lord, your servant is listening;

you have the words of everlasting life.

Alleluia!

1 Kings 19:16, 19–21

Elisha leaves the plough to follow Elijah.

Psalm 15(16):1–2, 5, 7–11

R. You are my inheritance, O Lord.

Galatians 5:1, 13–18

When Christ freed us, he meant us to remain free.

1 Samuel 3:9; John 6:68c

Speak, O Lord, your servant is listening; you have the words of everlasting life.

Luke 9:51–62

Jesus sets out for Jerusalem.

At the beginning of Mass:

The priest stands at the chair and, together with the whole gathering, makes the Sign of the Cross. Then he signifies the presence of the Lord to the community gathered there by means of the Greeting. By this greeting and the people’s response, the mystery of the Church gathered together is made manifest.

—General Instruction of the Roman Missal, §50

As we gather for Mass, we sign ourselves with the sign of the cross and acknowledge Christ’s presence among us, which is made possible by our coming together. We exercise our ministry of being God’s priestly people together, and we each contribute our special gift of faith. Yet, Christ relies on us to actually come together so that he can truly be present among us.

‘O God, who graciously accomplish the effects of your mysteries, grant, we pray, that the deeds by which we serve you may be worthy of these sacred gifts.’

—prayer over the offerings

St Paul urges us to use our freedom in Christ to serve one another through love. Guided by the Spirit, we ask God to hear our prayers for all who are not yet free from oppression, sickness or sin.

We pray for Pope Francis and all Church leaders. May their sensitivity and compassion encourage all Christians ‘to keep their hand on the plough’ in their witness to promote the kingdom of God among us.

Lord, hear us.

Lord, hear our prayer.

We pray for the people of the world who still suffer under the yoke of slavery. May they come to experience the dignity owed to them as human beings.

Lord, hear us.

Lord, hear our prayer.

We pray for all who are struggling to find food and shelter. May their burdens be lightened by the hands of generosity that stretch out to them in love.

Lord, hear us.

Lord, hear our prayer.

We pray for our faith community. May all that we do in our daily lives be done for the glory of God.

Lord, hear us.

Lord, hear our prayer.

We pray for …

Lord, hear us.

Lord, hear our prayer.

We pray for all who are sick in our parish and for all who have asked for our prayers.

We pray for those who have died recently and for all whose anniversaries occur at this time. May they enjoy the eternal fulfilment of the kingdom of God.

Lord, hear us.

Lord, hear our prayer.

God, our refuge and our hope, our hearts are glad in you, and our souls rejoice. Hear our prayers for the fullness of joy to reach all who have not yet found it. We ask this in Jesus’ name.

Amen.

by Sr Paula Moroney

It is Mary who stands at the focal point of history, where the Old Testament is fulfilled and the New Testament begins. Summing up the longings of the ages, she brought into the world the Saviour, Jesus Christ, and from those who believed in him the Church was born. Our destiny is thus bound up with hers, linked with her Son and one with him. It is she who guides us to the light of life as she enfolds us in a love that renews and inspires us.

As the Church solemnly proclaimed:

The Virgin Mary received the Word of God in her heart and in her body gave Life to the world. She is acknowledged and honoured as being truly Mother of God and Mother of the Redeemer … At the same time she is one with all who are to be saved. She is Mother of the members of Christ.

—Lumen Gentium, §53

Those outstanding women of the Old Covenant were familiar to Mary, who knew the story of Ruth, one of David’s immediate ancestors, whose faithfulness and loyalty to her mother-in-law were rewarded with a family of her own. Others like Deborah and Judith are remembered for defending their people with strength and bravery, and Esther for her courage and self-forgetfulness in pleading to save her nation at the risk of her own life. The bride in the Song of Songs, described with all feminine grace and beauty, was a figure of God’s predilection for his chosen ones, and Mary combined all such qualities. From the Sacred Scriptures, she learnt to read the story of her life by reflecting on the history of her people and the wisdom of the law and the prophets.

When the angel’s greeting came to her, she was lovingly disposed, attentive and prepared to do God’s will. She understood that she was singled out for a unique motherhood. Looking at Mary, a young maiden filled with grace, we see how one can accept the possibilities God offers when faith makes the leap to trust in the creative power of love. Her ‘Yes’ still left natural fear and hesitation. What could this mean? She accepted joyfully, willingly, and was reassured: ‘Do not be afraid. I am with you.’ It was the moment when the Eternal entered time. The Infinite and the finite met in her. God depended on her to fulfil the plan of salvation and still needs us today to carry it to our world. Faith allows the impossible to happen.

With joy, Mary hastened to journey across the hills to wait and keep Elizabeth company, helping her prepare for the birth of John, herald of the Saviour, in her service of love. The welcome she received was prophetic, affirming the blessings that would flow into the future. Yet joy was tempered with pain, for there was also loneliness and sensitivity in the delicate situation where her relationship with Joseph was tested. At first she could not share the secret she was holding in her heart. Joseph was troubled and of a mind to part with her discretely—a painful dilemma she had to bear alone. However, that was not to be, and when her time came to give birth, no words could describe the wonder and the mystery that took place in the poverty of a most humble setting, hidden from the busy world. Mary kept these things in her heart, pondering and treasuring them as precious signs.

There was to be foreboding and sorrow when they went to the temple to make the prescribed offering, and the old man, Simeon, met them with words that must have struck deeply as he foretold the pain this mother would share with her child. Then there was the anguish and fear when Joseph had to take them and flee in the night to protect the life of the child from Herod’s threat. When Jesus was twelve years of age, there were those three long days of waiting and searching. Did she remember this later, in those three days between death and resurrection?

In time of need and crisis, Mary was the one who unobtrusively spoke to Jesus then waited with confidence and trust, certain that he would intervene. He did provide the new wine in abundance for the wedding banquet when supplies had run out. Surely Mary still speaks on our behalf, aware of our needs, and her son never fails us.

In his most terrible abandonment and pain, she suffered with him on Calvary, where she waited courageously in steadfast fidelity and unfailing love. The days that followed were dark and frightening for his disciples, but Mary was there to encourage them and repair their shattered faith. This woman is there for us all. It is when we are overshadowed by the cross of suffering that we really know Mary is our Mother, standing beside us, a strengthening and comforting presence.

After the resurrection, the disciples were reunited and gathered with Mary in prayer in the upper room, awaiting the promise of the Holy Spirit. Ten days later, they went out transformed to give witness to God’s works, and the Church was born.

It is in prayer that we wait on God, in the prayer of the liturgy, when we come in the name of the Church, Christ’s mystical body, or alone in personal, silent prayer. At the same time, God is always waiting for us, respecting our choices and decisions. In prayer we commune most intimately with the Lord, opening ourselves to those deepest longings that often cannot be expressed in words. It is then that the Spirit pleads for us in ways beyond our telling. Our desire is in fact our prayer, St Gregory tells us. Those moments of quiet, unspoken prayer uniting us with God deepen our understanding and restore peace, going out to the troubled hearts of the world and giving true value to our lives.

God speaks to us as he spoke to Mary, silently, through inspirations in prayerful reflection, often through circumstances or through those around us. The Word that came to her at the annunciation was the living Presence of God in humanity. ‘The Word became flesh, and lived among us, and we saw his glory … full of grace and truth … For God loved the world so much that he gave his only-begotten Son’ (John 1:14, 3:16).

St Therese gathered inspiration from the gospels because she wanted nothing but truth and, in her final months, wrote a long poem in the form of a prayer addressed to Mary. The simple, ordinary years in Nazareth connected Therese with the Virgin Mary because her life, like ours, was made up of common events; she shared our sorrows, was eloquent in silence and joyful in poverty. She could then give her Lord a humanity because she was entirely his. She had nothing to give but herself, and God asked for nothing else. Therese summed it up: ‘To love is to give everything. It is to give oneself.’ Love is never wasted, and waiting with a loving attitude is opening ourselves to limitless possibilities and vast horizons. We are reminded of our own Australian Saint, Mary of the Cross MacKillop, who never stopped giving and who knew no boundaries.

In Carmel at the close of each day in Advent, we sing a beautiful medieval antiphon to Our Lady called the Alma Redemptoris Mater, in which she is called ‘the Gate of Heaven, and Star of the Sea’. This gateway is always open, and she waits for us, like the shining star piercing the darkness and pointing the direction to her Son, the Incarnate Word. The Word was already born in her heart when she became Mother and embraced the human family in her tender love. Now he is born in our hearts so that we can become bearers of this love to the world, whether it be in spiritual motherhood or physical motherhood. The most sublime wonders take place in the silence of ordinary, unnoticed events in everyday life and flow as grace on our world. Mary shows us how to wait on God, and she reveals how God is faithful, ever renewing the world with a wonderful, gentle and most powerful love.

Sr Paula Moroney OCDM is a Carmelite from the Monastic community at Kew, presently helping at the Canberra Monastery. She has been involved in liturgical music, and in writing and research inspired by her Carmelite spirituality, to express the richness, grace and beauty of the daily liturgy.

This article first appeared in The Summit in August 2010.

On 24 May, parishes are invited to mark Laudato Si’ Sunday, and to celebrate their part in the great progress the whole Church is making on its journey towards the seven Laudato Si’ goals set before us by Pope Francis to achieve ecological conversion. To assist with this, Catholic Earthcare Australia has produced a comprehensive set of liturgical resources, including bulletin notices, prayers of the faithful and hymn suggestions.

by Claire Renkin

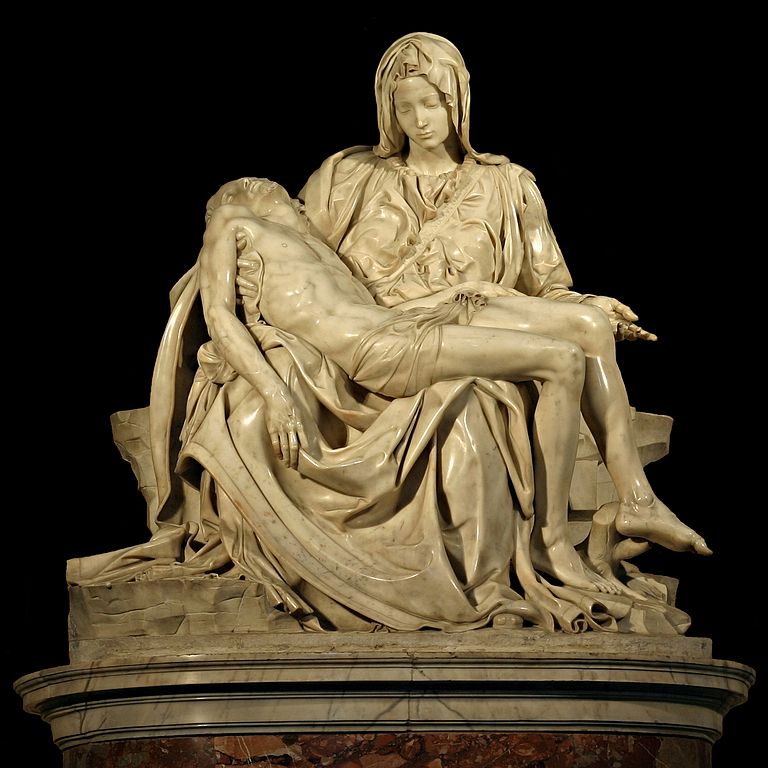

Although the gospels present us with disturbing accounts of the violence and brutality of Christ’s treatment, visually one of the most compelling images of Christ’s suffering portrays a moment of pain and loss that is stunningly gentle and serene. Michelangelo’s Pieta was sculpted by the young Florentine in the years 1497–1500. Originally the work was commissioned by a French cardinal, who wished it to be placed in his funerary chapel in St Peter’s. As we behold this sculpture, our gaze joins with that of Christ’s grieving mother, encouraging our eyes to move slowly over the slumped and lifeless form. Mary’s lap becomes a temporary resting place where, together with her, we pause in this moment between the deposition and the entombment. Michelangelo gives us a Christ whose idealised body recalls not only the influence of the classical past but also the phrase familiar from the canon of the Mass where we imagine Christ as a perfect and spotless victim.

For sculptors, the task of persuading us that a mother could plausibly contain the full-grown form of her dead son was a difficult one. Michelangelo convinces us of this almost physically implausible action by endowing the Virgin with garments that mass and swell around her form, so that she becomes able to support her dead child. The mood of profound and intimate contemplation is captured in the Virgin’s downcast gaze and slightly inclined head. But perhaps most of all what evokes the grief of the Virgin’s loss is her youthful beauty. Not only is Christ’s mother impossibly young; she also appears disturbingly remote. Here lies the spiritual and artistic power of Michelangelo’s genius. Not only do we reflect on this moment from the passion, but because of the incongruity between the Virgin’s ageless beauty and her maturity as a mother, we recall the more joyful images of her holding her newborn child. In collapsing the event of birth and death into this one timeless moment, Michelangelo evokes not only the desolation and sorrow of the Virgin at the moment she received her son’s lifeless body, but also the suffering of every mother who has felt the pain of the loss of a child.

Anne Hunt reminds us that often we tend to pass too quickly from Good Friday to Easter Sunday. In our meditation on the Passion, the starkness of the Good Friday liturgy can help us enter into the events of Christ’s suffering and death. But Holy Saturday is another story. It is precisely because, in one sense at least, nothing seems to happen that we are often left unable to find a way of understanding this harrowing period in Christ’s journey from death to new life. By focusing attention on the inertness of Christ’s corpse, Holy Saturday dramatises God’s total embrace of humanness.

Holbein the Younger’s Body of the Dead Christ in the Tomb, painted in 1521, reveals, with unflinching accuracy, an image of Christ’s body laid in a tomb. This image evokes both the physical and spiritual experience that Christ embraced for our sakes. Holbein shows us a body detached from any of the comforting details that so often accompany images of the dead Christ: no faithful mourners, not even lamenting angels to remind us of God’s merciful love.

Instead, Christ’s body is unceremoniously laid out in a shallow tomb. The emphatic horizontality of the space that encloses the lifeless body, together with the uncompromising rendering of the details of death (note how the face, hands and feet have already taken on a greenish hue), convince us of the mystery of utter annihilation that Christ descended into on Holy Saturday.

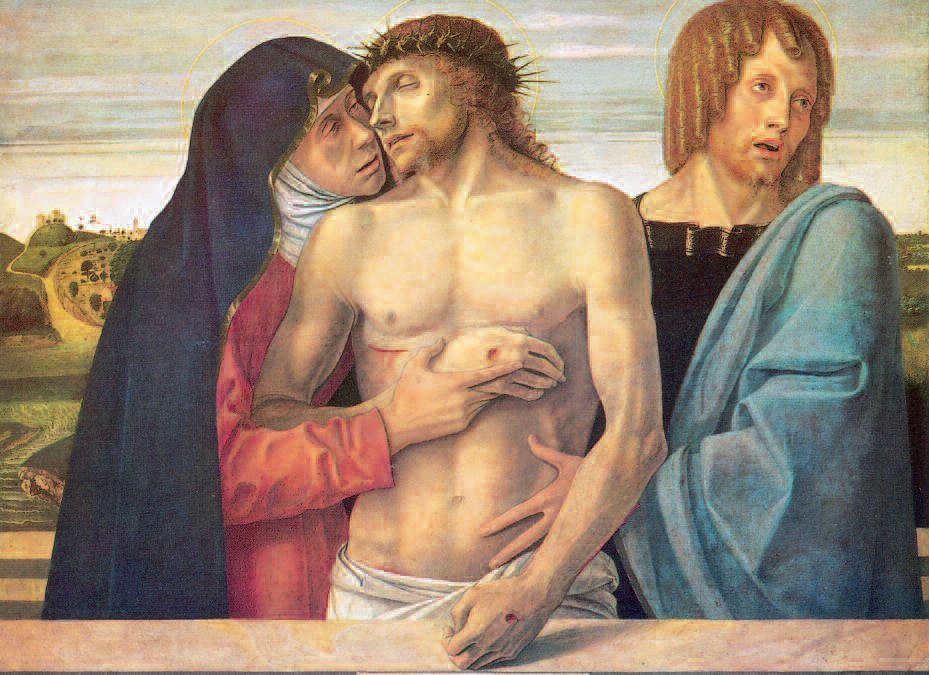

Giovanni Bellini (1430–1516), the great Venetian artist of the Renaissance, painted altarpieces, mythological scenes and portraits. Among his religious devotional works, the theme of the Pieta would occupy him throughout his long career. One of the most moving and hauntingly beautiful interpretations of this scene is the version dated between 1465 and 1470, now in the Brera Museum, Milan.

The dead Christ is held upright, supported by his mother and St John the Evangelist. They appear to stand behind a low stone parapet, which divides the space of the viewer from the sacred scene before us. Behind the figures we glimpse a landscape devoid of human presence—even the land is in mourning. Bellini captures with acute sensitivity to light and texture the grim reminders of Christ’s passion, from the disturbingly delicate crown of thorns to the fresh wounds in his hands and side. But it is surely the great master’s capacity to portray profound grief that moves us most. The faces of the mother and child are brought together before the moment of separation. Mary’s head turns toward Christ’s face as she gazes with the utmost sorrow on the exhausted face of her dead son. Her lips are parted as if she is about to utter a final lament for the suffering she and others have just witnessed. In a gesture of great tenderness, her hand supports her son’s lifeless arm. The overlapping hands in the centre of the painting offer a poignant testament to Mary’s steadfast love.

Lent, Passiontide, Easter, together with Christmas, comprise the great seasons of the Church. Arguably the visual arts have been more successful at capturing the drama of the passion than that of the resurrection. Although artists frequently include the resurrection in cycles of Christ’s life, inevitably it is the scene of the crucifixion or the lamentation that moves us. One of the exceptions to this generalisation is Giotto’s fresco of the resurrection from his cycle of Christ’s life in the Arena Chapel, Padua. Giotto painted the frescoes for the private chapel of Enrico Scrovegni between 1304 and 1313.

In a scene that combines majestic mystery and spiritual insight, Giotto visualises the resurrection as a theological event that is truly the culmination of the incarnation. The artist does not attempt to convey the mystery at the heart of the resurrection, Christ’s triumph over suffering and death. Instead we see two angels sitting on either end of the tomb. The hand of the angel on the left hovers outstretched, rhetorically confirming that the space both above and below stands empty. The other angel signals to us by gesture and glance where we are to find the risen Lord. As if enacting our response, the Magdalene stretches out her arms in a gesture that conveys both longing to touch her Saviour and understanding that she cannot. Bewildered in similar fashion, we behold the resurrected Christ. His upper body turns toward the Magdalen, yet we see by the placement of his foot that he also turns away from her. In this eloquently ambivalent pose, Giotto expresses the spiritual and human essence of the resurrected Saviour. Wholly human, alert and alive to our longings and desires, yet also divine, the conqueror of death and sin holds a banner in his left hand as he prepares to depart. He leaves us facing the same challenge as he left with the Magdalen. In the words of Hippolytus, third-century bishop of Rome, she was about to become ‘apostle and truth’.

Claire Renkin has been teaching art history and spirituality at Yarra Theological Union since 2001. Her teaching areas include the art and architecture of the early Christians and Byzantium, and the art and spirituality of the late middle ages. In addition to these topics, Claire co-teaches units on women doctors of the Church, death, dying and bereavement in art and spirituality, and the history of Mary in the Christian tradition.

This article was first published in The Summit in February 2004.

by Rev. Dr Frank O’Loughlin PP

The death of Jesus was not the only death that occurred on Good Friday! Something else died with him: the hopes and expectations of those who had become his disciples. In essence, the group around him came to an end with his death as that group that had its origin and meaning in him. They were all still alive as individuals and maybe even as a group of friends, but what had given them their purpose and an identity beyond themselves was gone with him.

The kingdom he talked about had died with him. For the moment, they were held together by fear and by the emptiness his absence left among them. There was no body for the women to anoint. The empty tomb soon lost interest for them: some of them went to see it, but there was little point to that. He was not there, even as a dead body. So the tomb faded into the background. His death was their death as his disciples.

They began to be roused and raised up by a word: a word from white-robed messengers of God, who sent them away from the tomb; words from women among them sounding hope, which they did not know how to believe.

It was all very precarious! There was nothing to get their hands on, no fulfilment of their earlier vivid and very concrete expectations of a kingdom, no obvious evidence of Jesus that they could show off to others. What did they have? Words sending them to discover ‘One who is risen, the one who is not here’.

Then it began to happen! They began to recognise him still among them—almost slipping in and out among them.

Two of them going to Emmaus, downcast, with their expectations dashed, are met on the road by a stranger who speaks words that set their hearts afire, who leads them to see. He leads them by starting with Moses and taking them through the Old Testament to see how it all leads up to ‘himself’. Their eyes are opened at the breaking of the bread and they recognise him. But he then disappears from sight!

So they came to recognise him strangely among them. So did they find their unity, their identity and meaning as his disciples by this discovery of him among them in a way unrecognisable according to their earlier expectations. It was different, strange, outside their expectations and plans.

They had to discover the different Jesus. They had to come to the discovery of this more tenuous, less obvious presence of Christ among them by giving up their very concrete, power-orientated expectations and plans.

He had been raised out of death by the Father, and he now raised ‘his own’ out of the death they had died with him.

He raised up a body for himself, the community of his disciples, his Church. This frail community, formed from the soil of the earth, he raised up by breathing his Spirit into it. Every time we celebrate the Eucharist, we celebrate and bring about this mystery of being his body, but it is most especially at the Easter Vigil that this wonderful mystery finds expression.

It is no accident that the Missal gives the instruction that the Easter Vigil is to be celebrated between the sunset of Holy Saturday and sunrise of Easter Sunday. It is to be celebrated during that blessed night that saw Christ rising from the dead. That night is on the one hand just night, but on the other hand also symbolically, liturgically, all that night and darkness can mean for human beings.

It is in the darkness that we gather in expectation of the rising of the sun who will shatter all darkness, the rising of that Son who has known the darkness with us and whose rising out of death will filter his light through all our darkness.

But we cannot see this victory, this unadvertised, quiet, patient victory—it has to be believed in! We have to discover this gift. We have to allow our hearts to be spoken to by his word and so come to recognise him in the breaking of the bread.

As we gather for the Easter Vigil, we begin following the light through the darkness as we are called upon to recognise that light with the simple words ‘The Light of Christ’, to which we respond, ‘Thanks be to God.’ For a long time, that seemed to me to be an insufficient response to such words. But how else could we put all our response into words? In heightened moments of appreciation, when words fail us, we often just say ‘Thank you.’

We are then taken through the Scriptures, where, beginning with creation, we see how all things lead up to himself. We are led again to proclaim that he is risen! This is the heart of this community: to know in faith that he is risen. This is the joy-filling news that we, such earthen vessels, hold for all the world to come to know. This is not just our rejoicing alone, but we call ‘all creation’ to exult ‘round God’s throne!’ We call upon the earth to rejoice as ‘radiant in the brightness of your king’. We call on our Mother the Church to exult in glory, for ‘the risen Saviour … shines upon you.’ We stand at the heart of the world on this night and gather everything around us to exult in the risen Saviour. This is not just for us. This is for all! But we are the body raised up by him, and to us the secret of the kingdom has been revealed.

It is on this same night that we, following on the custom of centuries, baptise those who are to become members of the Church. This is utterly fitting, because here we have the Lord adding to the numbers of those who believe; here we have the Lord raising up new members of his body. On this night of nights, it is right that we should celebrate Baptism and bring the baptised to confirmation and Eucharist, because it is the night when in celebrating his resurrection, we celebrate his doing—raising up a body for himself, which body is his Church.

As we look back through the history of the Church, there has always been great fragility and great strength in its life. Our history makes it clear that like all things human, we are indeed made from the soil of the earth. We are subject to human weakness and have often soiled the image of the Lord, who raises us up as his body. There is also the constant evidence of the Breath of Jesus in this same Church—that Breath that is his Spirit and that he keeps breathing into us, his living body.

The one who raised his ‘dead’ group of disciples to life after they had died at the time of his death is the same one who faithfully, unremittingly, will keep raising up this body for himself, now and in the future. He who raises us up is with us ‘all days, even to the end of the world’.

The pattern by which he gave life to his disciples after his death is the same pattern by which he will continue to give us life. He will take us through this present time of difficulty, seeming diminishment and feared death by helping us to see what must fall away in our expectations, presumptions and blindness. He will be active through his Spirit, enabling us to see anew and find new ways of being his disciples, as he did with those disciples on the road to Emmaus.

The resurrection celebrated by the Easter Vigil is Christ’s being raised out of death. It is his raising up of his disillusioned, fearful and lost disciples to be his body. It is his faithful breathing of his Spirit into the community of his disciples, on their pilgrim way to the banquet table of the Father’s kingdom.

This is a slightly adjusted version of an article first published in The Summit in February 2004.

The ACU Centre for Liturgy has launched its first online liturgical ministry training program for extraordinary ministers of Holy Communion, designed to support parishes throughout Australia, especially in rural communities.

Supported by the Bishops Commission for Liturgy, this new online training program is now open to confirmed Catholics who have been nominated by their local parish priest to train as extraordinary ministers of Communion for their community.

ACU Centre for Liturgy Director, Professor Clare Johnson, said the new program will transform the way parishes, schools and dioceses train lay people to use their gifts in service of the Church.

‘Our aim is to offer the best, high-quality training for liturgical ministers available anywhere in Australia, regardless of whether you’re in a remote parish in Wilcannia-Forbes or in bustling Sydney,’ Professor Johnson said. ‘Our comprehensive online training program has been developed by the nation’s leading liturgy experts and will prepare future liturgical ministers to offer their gifts for the glory of God and the benefit of their local community.’

The Diocese of Bathurst enthusiastically piloted this new program in late 2021, under the leadership of highly experienced liturgy coordinator and educator Cathy Murrowood, a member of the National Liturgical Council.

Ms Murrowood said her work in remote parishes convinced her that a hybrid model, combining in-person practical training with an online component, will meet the needs of today’s Church and support dioceses with limited training resources in this area.

‘I realised that people who are in remote areas don't have access to a lot of resources for liturgical training, and yet, being an extraordinary minister of Holy Communion is one service that Catholics are called on to perform every single week. This program provides a rich, accessible option for all,’ Ms Murrowood said.

Ms Murrowood, who received her master’s degree in theology from ACU, said it was logical to offer nationallyapproved liturgical ministry training programs online following an increasing interest in online courses since the beginning of the pandemic.

‘It’s the next step for the Church to be able to connect with a greater number of people and assist them to access high quality and consistent training for liturgy nationally,’ she said. ‘In this time of rebuilding and renewal, this new program provides an attractive and contemporary learning experience for liturgical ministers.’

Offering robust liturgical training could also improve the participation of the laity in the Mass and other liturgies as people who understand why they are doing what they are doing will inevitably celebrate better. ‘In the last couple of years Pope Francis has really called us back to understand that the liturgy belongs to the people, because it’s the people who participate in the liturgy every week. Liturgy’s the most important thing we do as Christians because it nourishes us for daily living,’ Ms Murrowood said.

This comprehensive multimedia training program will enable new and experienced ministers to gain the skills and confidence needed for this important liturgical ministry. The five-week online program provides rich and engaging content in a supportive environment. The program is led by an experienced liturgy instructor and features many opportunities for questions and interaction with others.

The skills and knowledge that are essential for extraordinary ministers of Holy Communion are explored through videos, readings, quizzes, audio, images and reflection-based activities. Zoom classes and a practical session ensure that participants become confident and effective ministers. The program promotes a broader understanding of liturgical ministry and the liturgy of the Church.

Participants from parishes, schools and Church organisations are endorsed by their pastor prior to registering. Engagement with the local community is a feature of the program.

To find out more and register online for the next available program visit: www.acu.edu.au/centreforliturgy/pastoral-training

For more information, contact the ACU Centre for Liturgy:

Email: centreforliturgy@acu.edu.au

Phone: (02) 9701 4751

The entire Catholic community in Australia is praying for guidance and wisdom from the Holy Spirit in this important time for our Church as we discern where God is calling us to be. To help us in this time of prayerful discernment, a collection of resources has been produced for use by individuals, families, schools, parishes and other Catholic communities.

The Walking in the Spirit resources include:

You can use these resources to encourage your community to engage in the Walking in the Spirit pilgrimage of prayer. Involve your parish and school. And don’t forget to invite your aged and frail to join the pilgrimage with their prayers.

Faith communities and groups across Australia are encouraged to use these prayers in a variety of ways, including:

Written by Fr Michael A Kelly CSsR

The seasons of Lent and Easter offer us an opportunity for personal and corporate repentance while offering us hope in a time of darkness. Grace is the gift of a loving God who shared the human condition and knows our potential for good and evil. Grace is also a gift that enables us to respond to the hospitality of a God who invites us into the embrace of a triune God with whom we are called to live life fully. What then might these bountiful themes mean for the homilist in these contrasting but complementary seasons of the paschal mystery? To answer this question, I will address a theme from each week of Lenten Cycle C and then draw upon the familiar Easter stories to see how these themes might be helpful to homilists and congregations.

Temptation is hardly a vogue word, but it is with us every day as we encounter familiar and new situations. The example of Jesus in confronting the devil offers us an opportunity to reflect on how we are tempted as Jesus was in Luke 4:1–13. Can we, like Jesus, resist the need for instant gratification (‘turn this stone into a loaf’), power over others (‘I will give you … these kingdoms’) and self-aggrandisement (‘angels … will hold you up on their hands’). The resistance of Jesus was the beginning of his public ministry, where he sought to care for the marginalised, empower others and challenge the powers of the day, who so often marginalised the most needy. What words give life to our congregations as they face these temptations?

Our world is not always a happy place, and every day the media confront us with news of disaster and tragedy. There is no future in depression, and it is only through grace that we are able to bring the black dog to heel and perceive a richer future. The transfiguration of the Lord may be a post-resurrection sign of hope of the ultimate triumph of Jesus, and although it didn’t convince the first apostles, it serves for us as a source of hope that our world can be transformed and we can contribute to that transformation.

Moses was a very reluctant leader, but his encounter with the ‘God of Abraham, the God of Isaac and the God of Jacob’ changed his life and was the beginning of one of the defining experiences of the Israelites—the Exodus—which would become a lifelong reference point as they both remembered and forgot how God heard their prayer and delivered them from the land of captivity into the land of promise. How might we invite the members of our congregations to recall those transformative moments when something other touched us, transformed us and called us beyond our limited realities? It is in these stepping-stone moments of our lives that we can revisit again and again to find resources for renewal.

Having asserted his right to independence, the younger son, after a dissolute lifestyle, ‘came to his senses’ (Luke 15:17) as he fed the pigs. Sadly, it is often only when we hit rock bottom that we come face to face with the consequences of our choices. Rehearsing the speech that he will make to his father, he resolutely sets out for home, but the homecoming is one that is beyond his imagination. In what is ‘totally unconventional behaviour for a dignified man of affairs in the Palestinian cultural world’ (Brendan Byrne, The Hospitality of God: A Reading of Luke’s Gospel, Sydney: St Paul’s, 2000, p. 129), the father embraces the son and celebrates his return by reinstating him in the family household. The older son’s resentment is quite understandable, but perhaps he has never seen himself as a son and has behaved as a contract labourer. We don’t know if he enters the family home to join in the communal celebration. If he does, it will be by an act of grace that releases his heart and enables renewed relationships.

Change often comes about in our lives when we take the time for reflection. We all have multiple life experiences, but if we are to learn from them, then we need to reflect upon them. Difficult experiences may force us to engage in introspection; positive experiences may also be savoured as we learn how we have been blessed in life. The woman dragged before Jesus is wordless in her shame and humiliation, but the searing words of Jesus to the scribes and Pharisees cause them to engage in a little self-reflection, and one by one they exit from the scene. The words of Jesus to the accused woman are not judgmental, but they do invite her to turn her life around. Hopefully, this encounter will enable her to make some changes in her life and she will learn, in the words of Paul, ‘the supreme advantage of knowing Christ Jesus my Lord’ (Philippians 3:8).

In a document entitled Preaching the Mystery of Faith: The Sunday Homily (November 2012), the US Catholic Bishops’ Conference states quite simply, ‘Ultimately the Lord’s Paschal Mystery becomes the basis of all preaching’ (p. 9). The rich liturgies of Holy Week penetrate to the heart of our faith, and are truly worthy of lectio divina, on which Benedict XVI focuses in Verbum Domini: The Word of God in the Life and Mission of the Church (§§ 86, 87). This ancient practice not only opens up the treasures of God’s Word, but is also capable of drawing us into an encounter with the one about whom the texts speak. Reflection on the Paschal Mystery, on death and resurrection, draws us to Jesus and the compassion of God, and through our own experiences of ‘the joys and hopes, the griefs and anxieties of the followers of Christ’ (Gaudium et Spes, § 1) to greater solidarity with humanity.

In Eastertide, we hear of the empty tomb, the post-resurrection appearances, and the dawning awareness of the first disciples that the Lord has risen and they are called to be witnesses. Confident that the Spirit of Jesus is with them, they find the courage that was so lacking during the trial and death of Jesus. Eastertide is the time when, under the influence of the Spirit of the Risen Lord, the themes of Lent come to fruition. In this season, our preaching should draw on the Lenten foci, which we have articulated, to enable us to reflect on our experience so as to grow in self-knowledge. We also rejoice that we have been forgiven our failings and that, immersed in the paschal mystery, we are a people of hope graced by a loving God. Our journey is not dissimilar to that of the first disciples, for we too, having experienced the Risen Christ, are called to mission, and ‘a homily that does not lead to mission is, therefore, incomplete’ (USCBC, Preaching the Mystery of Faith, p. 21).

As we attend to the Word proclaimed, we are mindful that the goal of the homily is ‘to lead the hearer to the deep inner connection between God’s Word and the actual circumstances of one’s everyday life’ (USCBC, Preaching the Mystery of Faith, p. 33). Homilies that are abstracted from the lives of the community have no power to transform hearts and minds. Homilies need learned exegesis but, without sensitivity to the contemporary context, risk being removed from the lives of the congregation. Ultimately, homilies that do not flow from the spirituality of a preacher who is steeped in a prayerful and thoughtful understanding of the Word of God will be unlikely to be fruitful.

God’s grace is not a magic potion but relies on what Catholics have called ‘natural grace’, which means human openness to the activity of God in the human heart. A graced response is a gift and a response to divine activity that enables us to commit ourselves to the mission of Jesus. The seasons of Lent and Easter bring us to our knees in acknowledgment of human failure and raise us to full stature in affirmation of the Risen Lord. May these seasons infuse in each of us new life.

Michael A Kelly CSsR is a Redemptorist priest who teaches at Yarra Theological Union, a college of the University of Divinity. He specialises in pastoral theology, religious education and homiletics.

This has been adapted from an article first published in The Summit in February 2013 for the Year of Grace.